The Doctrine of Signatures in TCM Explains The Power of Herbs

Who was the first person to eat a mushroom in the wild only to hallucinate or worse, croak?

Who first discovered the hard way that Conium maculatum, a plant that resembles wild carrot and celery, is actually poison hemlock—one of the most lethal plants on Earth?

Of course, not all primitive botanic experiments were epic failures. Whether through innate wisdom, hundreds of generations of trial and error, or both, plants have been successfully used as medicine since time immemorial.

If you’ve ever tried to wrap your head around how the actions of traditional Chinese herbs became known, there’s a fascinating theory: The Doctrine of Signatures.

What Is The Doctrine of Signatures in TCM?

How did ancient Chinese physicians discover the actions of various herbs? Did they just nibble on bits of every plant they came across and record their effects?

“Surge of Qi. Extremities feel warm. Yang tonic, for sure!”

Or was there a more organized method to their madness thousands of years ago?

A centuries-old theory called The Doctrine of Signatures may explain how certain herbs were selected for specific health concerns.

The Doctrine of Signatures maintains that “there are certain physical attributes of plants that serve as signs to indicate their therapeutic value,” explains Bradley C. Bennett in a research article published by the American Botanical Council.

Bennett is a professor of biological sciences and an ethnobotanical expert at Florida International University. He elaborates that these physical characteristics include shape, color, texture, and smell, which reveal their therapeutic value. Bennett alludes to the plant physiologist and historian R.H. True, who summed up the Doctrine of Signatures more succinctly: “Every plant having useful medicinal properties bears somewhere about it the likeness of the organ or of the part of the body upon which it exerts a healing action.”

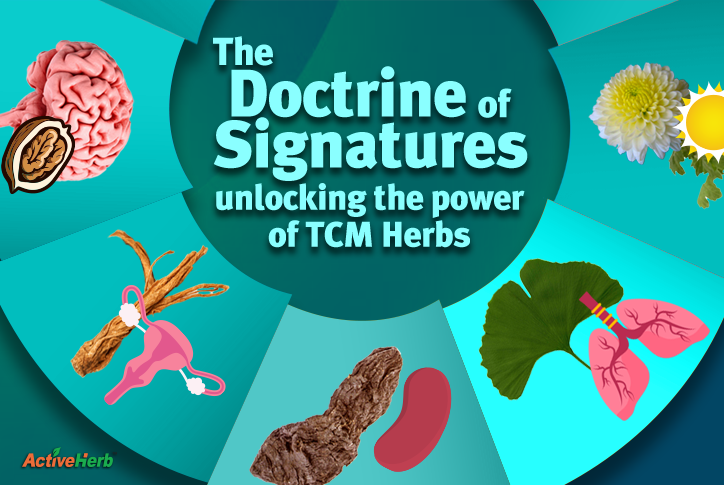

Examples of the Doctrine of Signatures in TCM

Walnuts

Walnuts are arguably the best example of the DOS in the West. This brain-boosting food resembles the two hemispheres of the brain. Even its shell is shaped like the human skull. Even in TCM, walnuts (Hu Tao Ren) are believed to support cognitive function.

Ginseng

The herbal root that looks like a little man, ginseng (Ren Shen) in Chinese means “essence of men.” Ginseng contributes to overall wellness and longevity by greatly tonifying the primal Qi. In other words, ginseng strengthens the body’s fundamental life force thanks to its root that looks like an “earth elf” as the herb is also referred to in China.

Chinese Angelica Root

Could it be that Radix Angelicae Sinensis (Dong Quai Root) is considered a uterine tonic because its root resembles the shape of a uterus? If so, it makes sense that it’s often prescribed to support a healthy menstrual cycle and gynecological health.

Rehmannia

If you do a Google images search for Rehmanni root (Shu Di Huang), you’ll notice that the root of this tuber has the shape of the physical kidney organ of Western medicine, which according to the Doctrine of Signatures explains why this TCM herb is used to support the Kidney organ system. More specifically, it’s used to strengthen Kidney Yin, Blood, and Essence, making it a key herb for addressing symptoms related to Kidney Yin deficiency such as low back discomfort, occasional dizziness, and hearing problems.

Solomon’s Seal

The tuberous roots of Solomon’s Seal (Yu Zhu) resemble a string of pearls or tears. What’s the benefit of Yu Zhu, according to the Doctrine of Signatures?

In TCM, this visual similarity is associated with the herb’s traditional use for moistening and lubricating the lungs and throat. If your Yang Qi is excessively drying you out because you’re running too hot, Solomon’s Seal may help generate bodily fluids and nourish cooling Yin energy. TCM doctors often use Yu Zhu for dry coughs, dry throat, and other respiratory conditions.

Chinese Yam

The rhizome—sort of like a root but technically a different part of the plant—of the Chinese Yam (Shan Yao) resembles the human spleen in shape. It’s no wonder that in TCM, it is used to strengthen the Spleen channel. This action strengthens digestion, which in turn promotes the production of Qi and Blood.

Ginkgo Biloba

Ginkgo Biloba (Bai Guo) leaves are fan-shaped. And what do fans do? They help ventilate, which according to the DOS, makes it an ideal herb for supporting the Lungs.

Bai Guo is included in the Guang Ci Tang formula for improving breathing compromised by a Cold-Wind invasion, Xuan Fei Ping Qi (Breathmooth™).

Chrysanthemum

The Chrysanthemum flower (Ju Hua) has a bright yellow center with white petals radiating outwards, resembling the sun. But in TCM, its properties are anything but scorching. In fact, Chrysanthemum possesses cooling properties that may clear heat from the Liver. It is commonly used in eye-related formulas because the Liver channel opens into the eyes. This makes Ju Hua, according to the Doctrine of Signatures, an herb that supports occasional redness, dryness, and irritation of the eyes.

Symbolic and Energetic Properties of Herbs

As stated, other physical attributes of herbs besides shape may explain their actions according to the DOS theory. Beyond the physical resemblance, there exists a symbolic and energetic meaning associated with certain plants. For example, a climbing vine may symbolize growth and upward movement. Thus, if someone has stagnant Qi in the Liver channel, manifested by anger, a climbing vine such as Jiao Gu Lan—an adaptogenic herb—may help support the Liver and promote Qi circulation.

The Doctrine of Signatures in TCM Conclusion

Western medicine may scoff at the Doctrine of Signatures, regarding it as an amusing folk sideshow. However, in TCM and many other medical systems, the DOS can be used as a valuable and intriguing tool in the arsenal of TCM practitioners. Rooted in ancient wisdom and observations of nature’s patterns, this fascinating theory provides valuable insights into the therapeutic properties of herbs and their potential applications in addressing specific health issues.

This is not to say TCM professionals dispense formulas to their patients solely based on DOS theory. We also have centuries of experience and modern research studies to thank for appropriate prescribing and dosing guidelines.